In the Making of Python Fitter and Faster

How Python's recent performance improvements work under the hood

Table of Contents

Python’s Performance Revolution

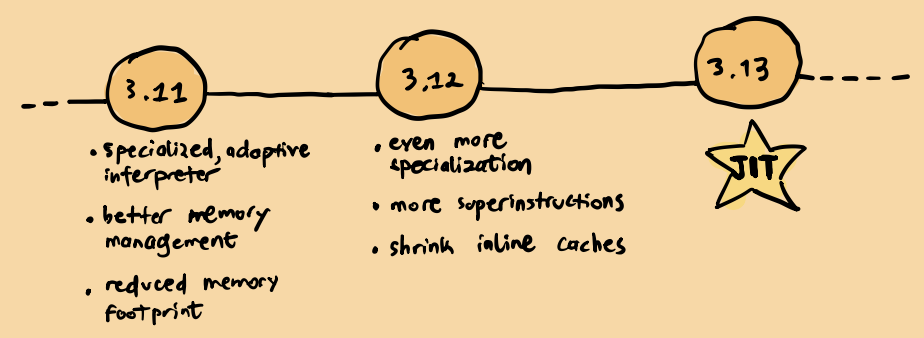

Since Python 3.11, there has been a strong, ongoing effort to make Python faster, and the results are clear. Performance improvements are real, and the work continues.

It’s both refreshing and surprising to see such significant speed gains in a language that’s nearly 30 years old.

But make no mistake: there’s no magic here. In my humble opinion, the success can be attributed to a few key factors:

Dedication: People, including Guido van Rossum himself, are working full-time on making Python faster. This commitment is crucial. It enables bold, low-level, core changes that drive performance improvements.

Talent and Effort: Mark Shannon has been grappling with this problem for nearly a decade, refining ideas and approaches over time. Including talented people like Brandt Bucher and many more…

Approachability: CPython’s codebase remains approachable and relatively simple, which fosters experimentation. Complex optimizations, like part of JIT compilation, have been implemented by two undergraduate students within two years, highlighting the fact that it does not require years of expertise to be around the development.

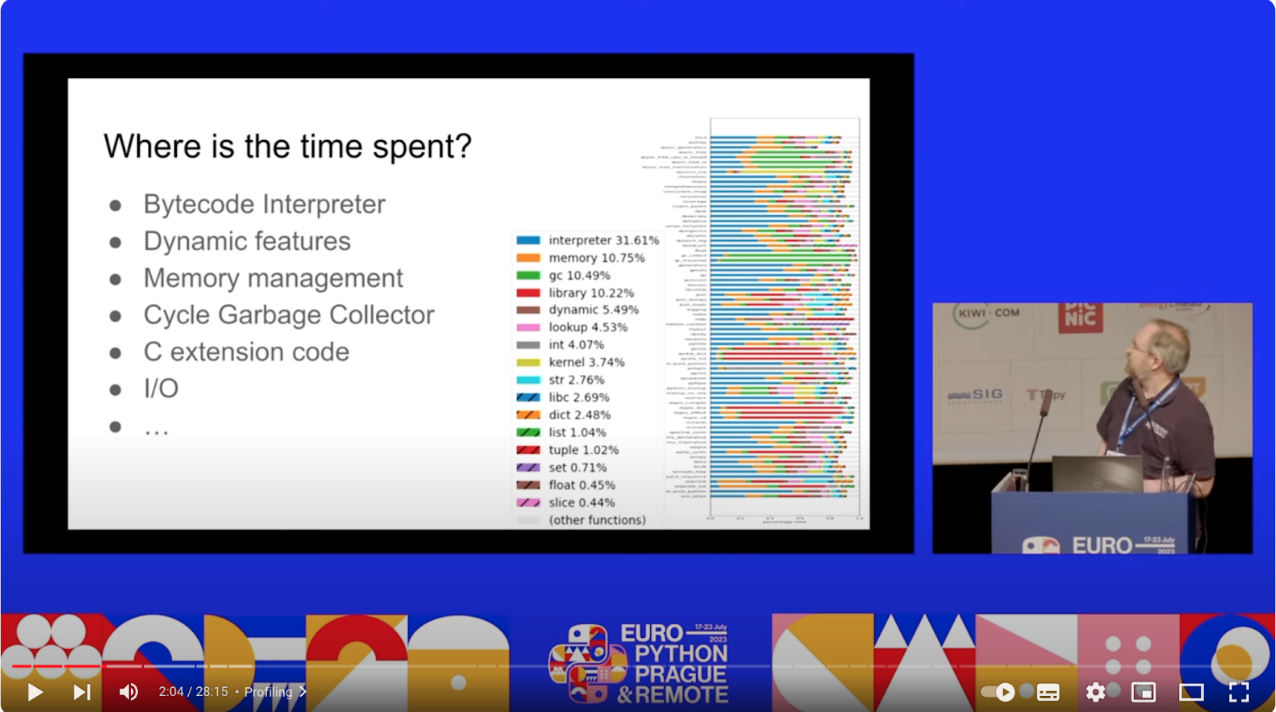

Accumulation of Quality Profiling Data: This aspect is somewhat overlooked in my opinion.

Python is widely used across many industries, which has led to an extensive accumulation of quality profiling data. This data, drawn from real-world production workloads like Instagram’s Cinder and platforms like speed.python.org and many more helps pinpoint hot spots.

This data-driven approach ensures optimizations are targeted where they matter most. There was no room for premature optimization from the start.

See Shannon’s talk, listing the execution time per component:

No Free Lunch: The Science and Sweat Behind the Speed

There’s no free lunch, though.

These improvements are the result of deliberate planning and research. The goal of a ~5x speedup was set even before implementation began.

Established languages like Node.js and Java, which have long used some of these techniques, also served as inspiration.

Before diving into the key techniques used, let’s first review the timeline to get a high-level view of the performance improvements:

1. Specialized, Adaptive Interpreter

Let’s see what “specializing” and “adaptive” mean with a real example. Think about the following code:

> def mul(x, y):

return x * y

> dis.dis(mul)

3 0 RESUME 0

4 2 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

4 LOAD_FAST 1 (y)

6 BINARY_OP 5 (*)

10 RETURN_VALUEPython VM is a stack based interpreter. As can be seen from the bytecode, to do an arithmetic operation, it first need to push the variables onto the stack and performs the operations there.

Let’ see what happens when we call this function few more times:

> add(2, 3.0)

> for i in range(11):

> add(2, 3.0)

> dis.dis(mul)

3 0 RESUME_QUICK 0

4 2 LOAD_FAST__LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

4 LOAD_FAST 1 (y)

6 BINARY_OP_ADAPTIVE 5 (*)

10 RETURN_VALUEFew changes already! Let’s inspect one by one:

0 RESUME_QUICK 0The first change is being the RESUME -> RESUME_QUICK change. It is a quickened form of RESUME: it skips some of the setup and check that RESUME performs.

This process is part of specialization, where the interpreter replaces one or more instructions with more efficient ones based on observed patterns. We call this faster variants superinstructions.

It’s important to note that Python specializes one bytecode at a time.

It doesn’t attempt to understand the broader context of what the application is doing to find the most optimal superinstruction for a particular problem. In compilers, such optimizations are possible—you can even implement something like strlen using a set of assembly instructions.

Python doesn’t take this approach. Its specialization is more limited, operating on a per-instruction basis.

The second is:

LOAD_FAST__LOAD_FAST 0 (x)In a stack-based VM, as one might expect, pushing and popping values to and from the stack are likely the most frequent operations.

Instead of issuing multiple LOAD_FAST instructions for variables like x and y, the interpreter merges them into a single instruction: LOAD_FAST__LOAD_FAST.

Let’s move on:

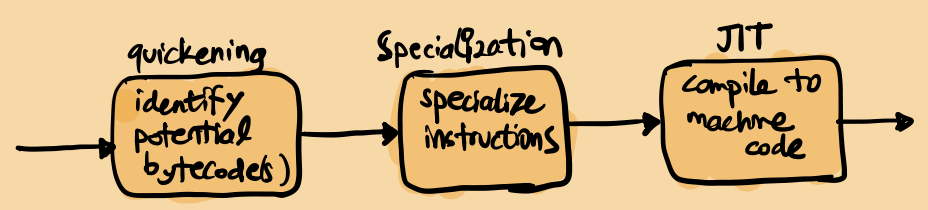

BINARY_OP_ADAPTIVE 5 (*)Notice how BINARY_OP becomes BINARY_OP_ADAPTIVE? This is again part of the specialization process, but here we are in an earlier phase: quickening.

During quickening, the interpreter identifies operations that could benefit from optimization.

In this case, the instruction is flagged as a potential candidate for specialization, but it hasn’t been applied yet. Why?

The answer lies in how we call it: we were adding an int (2) and and float (3.0). Modern CPUs have specialized instructions for efficiently handling arithmetic operations on integers, floats or even strings of the same type. If both operands had been of the same type, the interpreter would have used a specialized version of the instruction.

Instead, it marks the operation as adaptive, meaning the instruction might benefit from specialization in future executions if consistent type patterns are observed.

Let’s call our function 11 more times, but this time only with float’s:

> for i in range(11):

> mul(2.0, 3.0)

> dis.dis(mul)

4 2 LOAD_FAST__LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

4 LOAD_FAST 1 (y)

6 BINARY_OP_MULTIPLY_FLOAT 5 (*)

10 RETURN_VALUENotice the change? The adaptive instruction is gone. Interpreter became confident enough to optimize this code by replacing the instruction with a specialized one: BINARY_OP_MULTIPLY_FLOAT. This is called specialization.

There are tradeoffs though. One of them is memory– each specialization introduces a small memory cost, as the interpreter needs to store runtime information alongside the instruction. This is managed through an inline cache.

Inline caches are dynamically managed to avoid excessive memory consumption and the system falls back to generic execution if cache misses occur frequently. The PEP also provides a detailed analysis of memory usage related to this process.

Before we move further, please let’s pause to consider and appreciate what just happened. The interpreter optimized the code at runtime by collecting data and making bytecode-level adjustments based on that information, leading to faster execution! If this is not something impressive and inspiring, I don’t know what is.

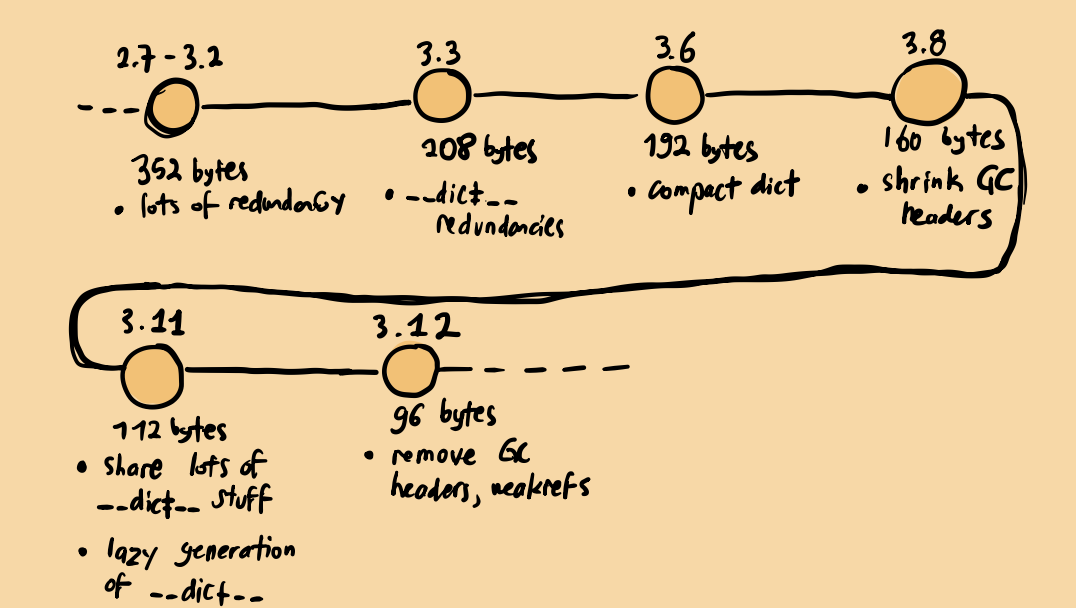

2. Better Memory Management

Less memory almost always means better cache utilization, thus optimizing for memory brings compounding benefits.

In this talk, Mark Shannon discusses how they reduced the size of the base Python object. Since everything in Python is an object, minimizing the memory footprint of Python objects is almost always beneficial. The talk goes into the finer details on how this was achieved over the years.

I’d like to provide a brief summary of what I learned from the talk:

In summary, object size has been reduced by approximately ~75% and memory reads to access a variable also reduced by ~60%.

This result serves as a real-world example on the compounding effect we mentioned earlier: the smaller object size leads to fewer indirections when accessing attributes, further enhancing performance.

Reducing memory is still a top priority and we will definitely see more improvements in this area. Python 3.13 introduced better heuristics for garbage collection (GC) cycles, leading to more efficient collection of cyclic references and reduced GC pause times.

3. JIT

JIT compiler is an experimental feature in 3.13 and PEP 744 describes how it works under the hood.

The previous improvements from the specialized, adaptive interpreter and having an inline cache per instruction paves the way for JIT compilation. Now, with JIT, we compile the specialized code to machine code.

From the release notes:

The machine code translation process uses a technique called copy-and-patch. It has no runtime dependencies, but there is a new build-time dependency on LLVM.

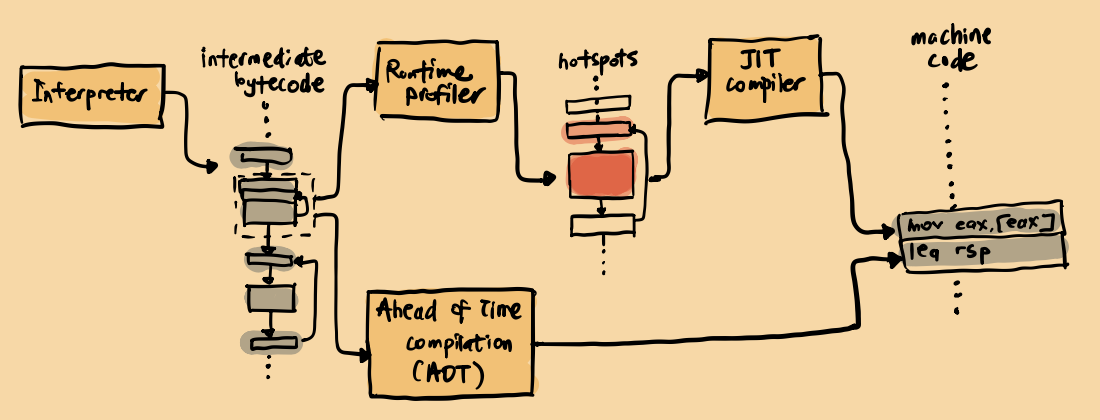

Before delving deep to explain what what this copy-and-patch means, let’s take a step back and have a 10.000 foot view on how JIT compilers work:

Interpreted languages like Java,Node.js and Python work on intermediate bytecode.

The VM executes this bytecode and with the help of an efficient runtime profiler, hot spots in the code are identified. These hotspots are then sent to JIT(Just-In-Time) compiler to be compiled to machine code.

For example, the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) leverages the LLVM framework to convert these hotspot bytecodes into machine code, allowing the runtime to switch to native instructions for faster execution.

Another method, called AOT(Ahead-Of-Time) Compilation, can also be used to complement JIT compilation. In AOT, parts of the code are optimized and compiled even before the program is run. Since there is no runtime profiling data available, AOT relies on static code analysis and heuristic techniques to predict potential hotspots.

Python, on the other hand, adopts a distinct and somewhat novel approach called “copy-and-patch.”

There is a paper elaborating this technique.

The concept is similar to traditional JIT compilers: Python performs a tracing step to identify potential hotspots and then converts them to machine code. Instead of dynamically compiling code, static pre-compiled bytecodes are copied into memory and patched during runtime. This means that as the program executes, only specific segments of the machine code are modified on-the-fly—hence the term “copy-and-patch.”

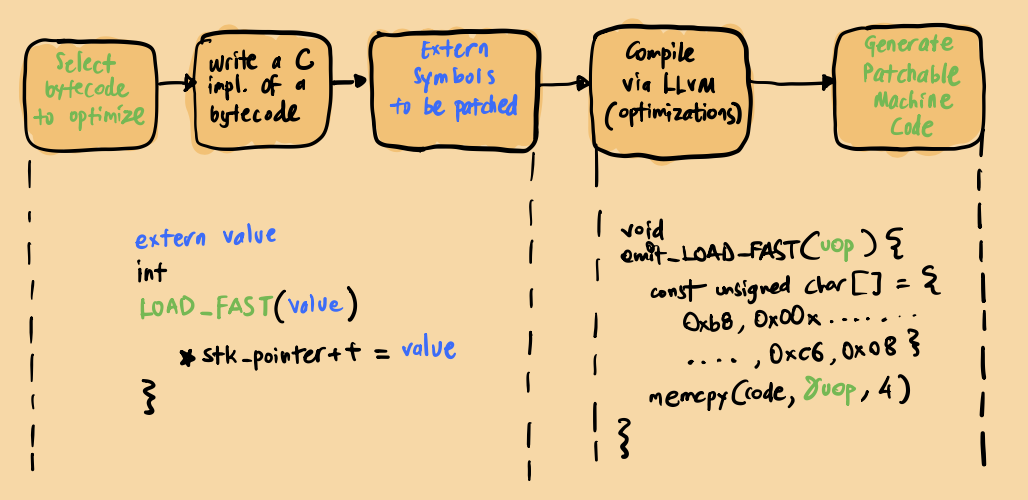

In this insightful talk, Brandt Bucher provides a perfect demonstration of how copy-and-patch works under the hood.

Here is my attempt to visualize the concept based on what I learned from the talk:

A specific bytecode identified for optimization is selected, and the corresponding C code is extracted to a separate file with modifications to enable runtime patching. This modified file is then compiled into machine code using LLVM. The resulting machine code is formatted into a C header file in a shellcode-like structure. The final product is a platform-specific, patchable segment of machine code that the JIT compiler can utilize as needed.

This approach has several benefits:

No Runtime Dependency: With copy-and-patch, there’s no need for a separate runtime compilation step, which eliminates the need for a compiler dependency in the interpreter.

Simplicity: This method achieves broad platform support by simply writing template JIT code in C. Python core developers don’t have to delve into platform-specific assembly, making maintenance easier and the approach more accessible to contributors.

Performance:Since there’s no full-scale compilation step, the overhead is significantly reduced. According to Brandt’s talk, the copy-and-patch method results in approximately ~100x faster code generation and ~15% faster execution compared to a traditional JIT toolchain.

While it may not match the performance of a handcrafted assembly JIT like LuaJIT in every scenario, it offers comparable compilation speeds and is only around ~35% slower in execution on certain benchmarks.

It’s still early days for this approach, but it’s undeniably a promising and more approachable alternative to implementing a full-fledged JIT compiler.

Crossing the Finish Line

The results speak for themselves.

From the official release notes(https://docs.python.org/3/whatsnew/3.11.html#faster-cpython):

CPython 3.11 is an average of 25% faster than CPython 3.10 as measured with the pyperformance benchmark suite, when compiled with GCC on Ubuntu Linux. Depending on your workload, the overall speedup could be ~10-60%.

Python 3.13 introduces the initial groundwork for JIT compilation, but it’s still in its early stages.

However, with Python 3.14, JIT is expected to mature significantly, bringing tangible performance improvements.

It’s also worth noting that these performance improvements don’t just apply to pure Python code. C extensions like NumPy, Pandas, and other popular libraries could also benefit from the faster interpreter loop and reduced function call overhead.

In summary, upgrading to Python 3.11 or 3.12 can lead to significant performance improvements, making these versions highly recommended for production deployments. This trend is set to continue with Python 3.13 and beyond. For instance, in my current company, Upsun, we almost always recommend users to use the latest version of their runtime.